OPINION

The cuts to Australia’s JobSeeker rate have been hotly debated, and it can sometimes be easy to get lost among all the different arguments about whether it’s high enough, or too high as is.

That’s why we’ve conducted an in-depth analysis of the upcoming cuts to our income support payments for those without work, looking at whether they make sense, how much they’ll cost, and what the experts think the rate should be.

Need somewhere to store cash and earn interest? The table below features savings accounts with some of the highest non-introductory and introductory interest rates on the market.

- Earn up to 5.20% pa by depositing $1,000 in the previous month

- No account fees

- Easy access to your money

In this article:

-

Mental health, homelessness made worse by low income support;

-

Does a lower unemployment payment drive people back to work quicker;

Background: Australia’s unemployment rate pre-coronavirus

Australia’s unemployment payment before the pandemic was called Newstart and had long been a divisive topic among politicians, economists and the public. Prior to the pandemic, the old Newstart rate was just $284 per week for a single person, the equivalent of $40 a day.

This rate, which hadn't increased in real terms (i.e. risen faster than the rate of inflation) since 1994, was heavily criticised by researchers and community groups as well as economists for being “punishingly low” and below the poverty line, which for a single person in 2020 is about $550 per week.

In terms of how well it replaced employment income for those unemployed for six months or less, Newstart was one of the lowest unemployment payments in the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), which includes 37 of the world’s leading economies. On that measure, Australia’s unemployment payment was below those belonging to New Zealand, Turkey, Romania and Slovakia.

According to Peter Whiteford, social policy expert and Professor at the Crawford School of Public Policy, our unemployment benefits have been inadequate for a long time, and the reason ours fails in comparison to other countries' is because of the structure of the payments.

“We have flat rate payments that don't have time limits on them, so theoretically, they're not designed to replace your past earnings, whereas everybody else in the OECD has a basic system that says: When you become unemployed, we’ll replace somewhere between 40% and 80% of your past earnings,” Professor Whiteford told Savings.com.au.

“What it means is the system is not designed to replace your past earnings. Even for an average worker or even a low paid worker, when you lose those earnings your income drops more than any other high-income country.”

While calls for the rate to be raised have been widespread, those in favour of it the way it was said a higher rate would discourage people from working and could lead to “widespread rorting”, with previous governments of both major political parties instead preferring to spend money on employment measures instead, to help people find work.

According to Professor Whiteford, when it comes to unemployment the current government is more concerned with ideology over economics, although historically it’s been an issue spread across both major parties.

“Essentially the unemployed are very low on both Labor's and the Coalition's priorities, but in the long run it [the rate of payments] doesn’t make any sense because we've reached the stage where it probably does hinder people from looking for work,” he said.

“In the last election, Labor said they would have an inquiry to look at it [Newstart], but the Government’s resisted that for a long time, and up until this year it was all about getting the budget deficit down and achieving a surplus.”

However, when COVID first hit, the Morrison Government did end up significantly increasing the Newstart payment - albeit via a temporary supplement.

JobSeeker saw the unemployment payment double

Those who wanted the unemployment payment increased got their wish in March, although they might have wanted it to come under better circumstances. The economic shutdowns and restrictions imposed by the Government in early March led to the introduction of JobSeeker, which replaced the old Newstart payment and effectively doubled it to $1,100 per fortnight through the addition of a $550/fortnight ‘coronavirus supplement’.

Initially lasting for six months alongside the JobKeeper scheme, as many as 1.6 million workers were on the increased payments at the height of COVID shutdowns as the unemployment rate peaked at 7.1%. This cost around $14 billion in total, small pennies compared to the $500 billion spent so far in response to the crisis.

However, based on the data so far, it looks to be money well spent.

JobSeeker has been a very successful scheme so far

“The Government is taking unprecedented action to strengthen the safety net available to Australians that are stood down or lose their jobs and increasing support for small businesses that do it tough over the next six months.

“These extraordinary times demand extraordinary measures.”

- Treasurer Josh Frydenberg announcing the doubled JobSeeker rate, 22 March 2020

At the beginning of the crisis, and again throughout the first few months of the scheme, the increased JobSeeker rate along with JobKeeper received mostly bipartisan praise from both major parties, as well as social groups usually critical of the Morrison Government. Australian Council of Social Service CEO Cassandra Goldie, for example, called it “a huge relief”, and welcomed the doubling of the unemployment payment.

And to the Government’s credit, these schemes did prove to be mostly successful. If it weren't for these income support measures, the COVID-19 recession would have almost doubled the number of Australians living in poverty from just over 3 million people to 5.8 million people, but instead, the number living in poverty fell to 2.6 million people in June.

Almost half a million households were spared from falling into housing affordability stress; the stimulus payments helped improve our average incomes by $5,000 over the COVID period; and the household savings rate skyrocketed to 19.8% from 2.5%, which according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics provides households with a "considerable buffer to draw upon in coming quarters".

However, despite this success, the intention of the Government was always for these schemes to be temporary. Speaking to the National Press Club in May, Prime Minister Scott Morrison said:

“At a now anticipated cost of more than $150 billion [including JobKeeper] in just six months, all borrowed against future tax revenue, these supports can of course only be temporary,” he said.

In another press conference, Mr Morrison has also said that a doubled unemployment benefit could be a "disincentive" to look for work.

How much is JobSeeker being cut by?

Sure enough, in July, the Federal Government announced that the JobSeeker coronavirus supplement would be extended beyond September till December, but at a reduced rate of $250, taking the total JobSeeker payment down to $815 a fortnight.

Then again, in November, the Government confirmed it would be extending the supplement through to March 2021, but from December 2020 it would be reduced to $150, taking the total JobSeeker payment to $715.70 a fortnight for a single person.

This extended support from the Government would cost an extra $3.2 billion, with the Prime Minister once again saying people needed to get back to work. "Australia is safely reopening and it needs to remain safely open. Jobs are returning. Job advertisements have doubled since May,” he said.

These two cuts were met with scorn by the usual detractors, with some arguing that the boosted JobSeeker payment should have been made permanent, although Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese had previously said he didn’t think the payment should be maintained at its $1,100 per fortnight rate.

To justify his JobSeeker cuts today, the PM said “we cannot allow the lifeline that has been extended to also now hold Australia back”.

— Jim Chalmers MP (@JEChalmers) November 10, 2020

On what planet does helping the growing ranks of the unemployed, in a recession, hold the country back? #auspol

The Shadow Treasurer weighs in on Twitter.

So, is cutting JobSeeker a good idea?

There are arguments for and against cutting the rate of JobSeeker, which are explored below.

Does a higher JobSeeker rate stop people from working?

“Jobseeker rates should be sufficient for an unemployed recipient to pay their basic needs, but not high enough to discourage active job hunting. To maintain a low level of structural unemployment increasing rates beyond the pandemic crisis is not recommended.”

- Joaquin Vespignani, Associate Professor, University of Tasmania School of Business and Economics

There is mixed data to suggest if this is true or not. There’s been plenty of examples splashed around the media here and there about businesses struggling to find workers. Employment Minister Michaelia Cash said more than half of the businesses surveyed by the National Skills Commission (NSC) who had reported recruitment difficulties back in May cited a lack of applicants, while the Prime Minister warned that the higher payments meant people were less likely to take on extra shifts.

“We are getting a lot of anecdotal feedback from small businesses, even large businesses, where some of them are finding it hard to get people to come and take the shifts because they’re on these higher levels of payment,” Mr Morrison told 2GB

The latest NSC survey of employers from November 2 to November 27 reported that 47% of employers are recruiting, of whom 40% have had difficulty recruiting. Of those that reported difficulty recruiting, around 35% cited ‘lack of applicants’ as a reason.

However, many of the cases of employers being unable to hire workers are anecdotal and don’t necessarily represent the broader jobs market and behaviours of JobSeekers.

For example, it was widely reported in the media a few months back that JobSeekers should look to picking fruit on farms as a way to make money. But as the New Daily reported, AgriAus had more than 1,500 applicants for farm work but was unable to secure even one of them a job due to farmers’ preference for foreign workers who provide cheaper labour.

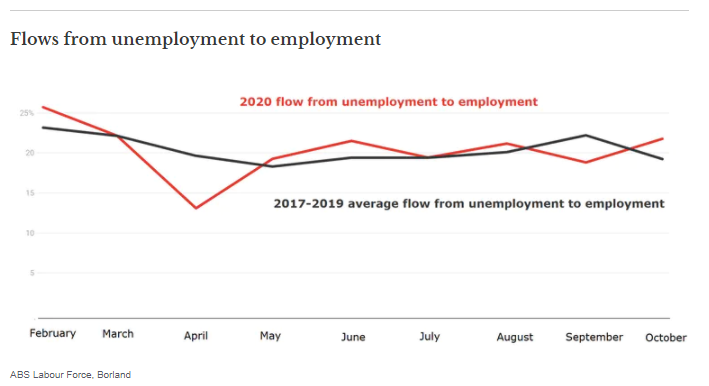

Recent research has also been conducted by the University of Melbourne into this hypothesis, and according to the research’s author Professor Jeff Borland, there is little evidence to suggest a financial disincentive for jobseekers to shift into employment should result from increasing JobSeeker.

“First, the increase (from $282.85 to $407.85) would leave JobSeeker recipients at the very bottom of the distribution of earnings of full-time adult workers – the bottom percentile. This means 99 out of every 100 full-time jobs would pay more,” Professor Borland said.

“Second, it is well-known that a substantial incentive for work (in some studies of equal importance to the financial incentive) comes from the social and psychological benefits - which will be unaffected by an increase in JobSeeker.

“Third, there is no evidence that the higher rate of JobSeeker (with the COVID supplement) has caused an increased vacancy rate or reduced flows from unemployment to employment (either in aggregate or for the young).

“To anyone who argues that a substantial increase in JobSeeker would cause an appreciable increase in the disincentive to work, the question has to be asked: What is your evidence?”

Based on this data, it would appear all but the lowest-paid jobs still pay more than the unemployment benefit - before it gets cut even further - and even at its highest point during the pandemic, the benefit payment was only 75% of the minimum wage. Therefore, employees have a marginal propensity to keep looking for work, while there are also social and mental benefits to working that being unemployed can’t give.

Based on this data, it would appear all but the lowest-paid jobs still pay more than the unemployment benefit - before it gets cut even further - and even at its highest point during the pandemic, the benefit payment was only 75% of the minimum wage. Therefore, employees have a marginal propensity to keep looking for work, while there are also social and mental benefits to working that being unemployed can’t give.

Higher Jobseeker rates lower the cost of mental health, homelessness and more

“There is now considerable evidence that over the past 20 or more years the level of the safety net provided has eroded and it is not now adequate to enable recipients to avoid severe hardship, instances of hunger and in some cases homelessness.”

- Professor Margaret Nowak, Curtin University School of Economics, Finance and Property

The Productivity Commission’s mental health report, released recently on 16 November 2020, conservatively estimated that the cost of mental illness to the economy each year is between $200 billion and $220 billion, which is almost what we spent on social services like JobSeeker and the pension ($227 billion all up) this financial year.

The report makes a clear connection between poverty and mental health, saying “it is clear that there is an association between socioeconomic disadvantage and mental illness that contributes to social exclusion [and] social exclusion is not completely alleviated by the income support safety net … In some situations [it] may be exacerbated by aspects of the income support system.”

Upon the release of the report, the Prime Minister committed to making changes to address the mental health epidemic, saying “we need to go far beyond the health system, and we need a whole-of-economy approach.”

Yet the commitment to cutting the JobSeeker supplement remains, despite research coming out at around the same time finding the planned cuts could push as many as 190,000 people - including 50,000 children - into poverty, based on the eventual $50 per day rate.

“No other government has ever lifted so many people out of poverty so quickly than the Morrison Government did with the Coronavirus Supplement," Matt Grudnoff, senior economist at The Australia Institute said.

“It [the reduction] will result in hundreds of thousands of Australian families being pushed below the poverty line—it means a struggle to put food on the table, to pay rent or service mortgages, and it will cause acute pressure on people in an already turbulent time."

This could also have dire effects on the rental and housing markets as I reported recently. Anywhere between 5% to 15% of all renters could face evictions over unpaid coronavirus rental debts. That’s 324,000 - 973,000 people Australia-wide. For those on JobSeeker struggling to meet their housing obligations, or needing to find a new place to live, rents all across Australia will likely be unaffordable or “extremely unaffordable”, which could potentially result in a surge of homelessness.

A single person on JobSeeker would earn just over $20,000 per year - deeming the whole of Australia unaffordable to extremely unaffordable. report, interactive map media releases for states here: https://t.co/yJJARJpBE4#mediarelease #australia #affordability #housing #renting pic.twitter.com/OUbXmcATCQ

— National Shelter (@NationalShelter) November 30, 2020

An increased rate of JobSeeker could help alleviate a significant chunk of both housing stress and mental health issues across the country.

Does a lower unemployment payment drive people back to work quicker?

The main argument (in the absence of substantial modelling) for cutting the JobSeeker rate is to get Australians back into work as quickly as possible. This makes sense on the face of it when you consider we currently have an unemployment rate of 7.0% (as of October 2020), with 960,900 unemployed people and a youth unemployment rate of 15.6%.

However, Deloitte Access Economics Partner Chris Richardson says it will be years before our unemployment rate returns to what it was pre-COVID.

“It’s good news that the Government has made it clear that unemployment is now Public Enemy Number 1, and that it will keep the budgetary pedal to the metal until unemployment is comfortably back under 6%,” Mr Richardson said.

“But the matching bad news is that we don’t see unemployment back to 6% until early 2024, and that ‘comfortably under’ looks set to be late 2024. That’s a long time between drinks.”

With entire industries decimated by shutdowns enforced by state and federal governments, punishing people for being out of work through no fault of their own doesn’t seem to make much sense, and in situations where people have to re-train themselves to find new work, for example, a higher JobSeeker allowance would help them do just that. This is especially true when you consider there are around 12-13 people on JobSeeker for every job vacancy at the moment, a figure which increases to more than 100 for certain entry-level jobs.

“They’re facing cuts to their payments, and they’re being forced to jump through hoops and apply for jobs. But our research shows the jobs just aren’t there,” Anglicare Australia Executive Director Kasy Chambers said.

There’s plenty of evidence to suggest that a low social safety net actually makes it harder for people to find work. The OECD pointed this out in its review of Australia’s social net a decade ago now, as paying for things like disability care and childcare can make it harder to apply for jobs. The OECD’s review said the old Newstart rate had fallen to the point where “questions could be asked about its effectiveness in providing sufficient support for those experiencing a job loss, or enabling someone to look for a suitable job.”

“Searching for jobs takes time and costs money. More income from JobSeeker means less financial stress and more ‘bandwidth’ to commit to job search, and more resources such as the ability to pay for transport to and clothing for interviews,” Professor Jeff Borland of the University of Melbourne said.

So if the government wants more Australians to apply for jobs, making it harder for them to do is not the answer.

How expensive is raising JobSeeker payments?

With the initial cost at around $14 billion, the extra extension of JobSeeker at a reduced rate from January to March is estimated to cost around $3.2 billion by the Department of Social Services.

The cost of these programs has long been a reason for their eventual tapering off. Treasurer Josh Frydenberg mid-pandemic said the schemes couldn’t afford to go on forever. "Australians know there is no money tree. What we borrow today we must repay in the future," he said.

But, at around $3 billion, there’s an argument to be made that this payment is small fry compared to the remainder of the money Australia has spent so far on stimulus (around $500 billion).

Recent modelling has also been conducted by various groups showing how comparatively cheap maintaining a higher level of income support is. Research by Deloitte back in September found rolling back the coronavirus supplement would reduce the size of the economy by $31.3 billion and see an average loss of almost 150,000 jobs over the following two years (although that was based on the rate going back to the pre-COVID level, not the $150 supplement level we’ll have at least till March 31).

BDO research meanwhile found this is significantly cheaper than the government’s tax cuts, rolled through in the 2020-21 Federal Budget, which are estimated to cost around $40 billion a year by 2026-27.

So the argument remains: If a higher level of JobSeeker is too expensive, then what about the alternatives?

"Providing people without paid work with enough to get by is highly effective economic stimulus, as they have little choice but to spend straight away on essentials," Deloitte Access Economics Partner Nicki Hutley said.

“People on higher incomes have the option of saving, which many are doing right now given the uncertainty of the pandemic. This is why other measures, such as income tax cuts, would not be as effective in getting us out of this recession."

Boosting the JobSeeker rate was one of the most popular stimulatory options proposed by a number of leading economists back in September, with 51% of the 49 surveyed by The Conversation saying it would be the most effective, second only to social housing construction (55%).

"Of course work incentives matter but the rate was so low that it was counterproductive - interfering with job search and job readiness. Boosting the payments now would also be good stimulus because we know that every dollar will hit the economy," Grattan Institute CEO Danielle Wood said.

Source: The Conversation.

Can we afford the extra payments?

There is, of course, the case to be made, as Treasurer Frydenberg said above, that all this extra stimulus spending will have to be repaid someday, by our children or grandchildren. Australia recorded a deficit of more than $213 billion in this year’s budget, and gross debt (the money a government owes) is now almost $800 billion. The argument against constantly printing money is that it leads to rampant inflation, and the theory that governments can create as much money as necessary (i.e Modern Monetary Theory) has been rejected by a lot of mainstream economists (although some support it too).

On the other hand, there are those that argue that not all debt is bad debt, and that the government should continue to borrow what it can now to boost the economy at a time when interest rates are at record lows (the cash rate sits at just 0.10%), and the Reserve Bank itself has warned the government not to turn off the stimulus tap.

“If this debt-driven spending is targeted at job creating and productivity-boosting initiatives, it has the potential to drive economic growth and boost future government revenue over the long term in excess of the cost of debt incurred,” PWC said in a recent report.

According to PWC, debt-driven stimulus can be beneficial if it meets these criteria.

According to Grattan CEO Danielle Wood, debt has never been cheaper, and with the real interest rate the government is paying on bonds being negative, it will effectively be paid to borrow.

“These very low-interest costs change the dynamics of managing debt we accrue now. Investments that boost future growth – including spending to reduce unemployment and close the output gap – will pay for themselves,” Ms Wood said.

“There are many urgent and valuable priorities for government spending right now, such as permanently raising JobSeeker, boosting child-care support and building more social housing. More debt might impose a small cost over a very long time…but the cost of insufficient stimulus and a prolonged recession would be vastly bigger.”

Deloitte’s Chris Richardson also argued in favour of the need to continue spending (wisely).

“Australia’s recovery is very reliant on governments going hard and going smart: Going smart means reforming…going hard means that the federal and state governments need to keep up their spending,” he said.

“(It) underscores a key point: The need to let growth in the economy shrink the debt, rather than letting attempts to shrink the debt hold back the economy.”

If you need more convincing, the Reserve Bank Governor himself said something similar in July, saying "it is the right thing to do in the national interest” for state and federal governments to borrow in order to create jobs, and that financing was not a constraint on government spending at the moment.

So what should the unemployment allowance be?

So there are plenty of arguments in favour of further increasing the JobSeeker rate, and it was already a hot issue before coronavirus. But just how much it should be increased by is up for debate.

What do social groups think?

The COVID level of $1,100 per fortnight is at the extreme end of the scale; there aren’t too many economists arguing for a permanent increase to this level. Those who do argue for an increase to near this level are the likes of social groups such as ACOSS.

“The reality is that doubling the previous unemployment rate to $550 per week has put people just above the poverty line. This has transformed lives, and provided a lifeline to a flagging economy,” CEO Cassandra Goldie said.

What do business groups think?

Other industry leaders, such as Australian Industry Group chief executive Innes Willox, who represents 60,000 employers, are of the opinion that other alternatives should be considered, such as increasing rent assistance payments before any drastic increases to JobSeeker.

"If there is to be a reassessment of the JobSeeker base rate, account should be taken of the degree to which any change increases work disincentives," Mr Willox said, before arguing that raising things like rent assistance supplements would better target those in need.

The Business Council of Australia (BCA) meanwhile submitted to the Federal Budget that JobSeeker should be benchmarked to more than 75% of the aged pension, which is around half the minimum wage. At 80% of the pension, the base rate would be about $690 on top of any COVID supplement.

JobSeeker was actually above the age pension during the pandemic. Source: Ben Phillips ANU, Services Australia

What do economists think?

In November 2020, The Conversation and the Economic Society of Australia asked 45 economists what they thought the JobSeeker rate should be, with not one of them expressing concern about the budgetary cost of any increase.

Of these economists, which include former and current government advisers and a former member of the Reserve Bank board, all but four advocated for a permanent increase to the base rate. The most common response was a $100-$150 per week increase (37.8%), while $50-$100 was also popular.

Economic Society of Australia/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Of the four that said it should be kept at the old Newstart rate of $287.25 a week, reasons included farmers struggling to find workers or those on JobSeeker being disinclined to work, or that JobSeeker should simply be indexed to inflation.

“So far as indexation is concerned, we should adopt the Swiss indexation formula of half the rise in wages plus half the rise in prices. This should apply to both unemployment benefits and government pensions. In the long-run it would ensure that unemployment benefits do not drift down relative to pension benefits.”

- Geoffrey Kingston, Professor of Economics, Macquarie University.

Others arguing for a small weekly increase of $0-$50 advocate that more vulnerable recipients should get higher payments.

“The needs of the elderly are potentially higher (e.g. due to higher health care expenditures and care support), which justifies as more generous indexing. Yet, the original Newstart rate of $287.50 appears too low for single mothers etc.

- Stefanie Schurer, Professor of Economics, University of Sydney

Around 30% of the economists surveyed believed a moderate weekly increase of $50-$100 was required, with a common reason being the payments should be indexed to wages or even the pension so “this issue never arises again”.

“In recessions and times of higher unemployment, JobSeeker could have a supplement (as indeed it has had recently); in booming economic conditions, when it is easier to find work, this supplement could be scaled back and extra support provided instead not in monetary form but towards in-kind assistance for those still remaining in unemployment even in times of low unemployment - who are more likely to be our long-term unemployed.”

- Gigi Foster, Professor, Director of Education, UNSW

The most common option was a weekly increase of between $100 and $150. Reasons for this included the current rate being inadequate compared to increasing living standards and material mental health consequences. Others said the government should also look into getting rid of excessive welfare requirements.

“To this end, a useful (and easily implemented) reform would be the reduction or elimination of poverty traps in welfare payments. Such reforms would give welfare recipients greater financial rewards to seek the available work, and thereby increase the workforce in areas where there may be shortages.”

- Hugh Sibly, Senior Lecturer, Tasmanian School of Economics and Business

Finally, the biggest increases suggested by economists were by more than $150 per week, or $300 a fortnight. Some recommended going as high as $180 a week higher, with increases higher than this starting to impede on someone’s marginal propensity to work. Below this amount can be an impediment to the unemployed finding work and maintaining a decent standard of living.

“The reduced Jobseeker allowance is insufficient to cover recipients' subsistence and maintenance costs. It also should not be forgotten that recipients' expenditure from the allowance not only helps them maintain their health but also feeds back into the economy.”

- Alison Booth, Professor of Economics, Australian National University

So should JobSeeker be permanently increased?

Based on the mountain of evidence presented throughout this piece (and congratulations and thank you if you’ve made it this far), it would appear that the general consensus among a significant number of economists is that the pre-Coronavirus unemployment payment, Newstart, was far too low, and a substantial increase was long overdue. To the government’s great credit, it acted quickly and did just that, saving hundreds of thousands from poverty and destitution during our biggest financial crisis in decades, maybe since the Great Depression.

[See also: How does COVID-19 compare to previous recessions?]

However, the evidence also seems to suggest that standing by the planned JobSeeker supplement cuts to $150 aren’t great economics. I reached out to both the Treasury and the Department of Social Services (DSS) to ask what modelling had been used to reach this decision and was not given a direct answer.

“As the economy gets back on track, the Government is focused on striking a balance between temporary, enhanced support for unemployed Australians while the labour market remains shallow at the same time as incentivising people to take up work where and as it becomes available,” a DSS spokesperson said.

By raising the rate to the thresholds suggested by numerous experts in this article, whether that’s by $100 per week, $150 per week, more than $150 per week or by indexing to wages growth, Australia can go a long way to:

-

Improving our nation’s mental health while also spending fewer Federal dollars on it

-

Help people who lost jobs from the pandemic to remain afloat, without hampering their ability to find work

-

Helping people avoid poverty by allowing them to pay for their families essentials without having to sacrifice

-

Keep the housing market from plummeting while also helping renters and homeowners avoid housing stress

-

Stimulate and improve the economy faster by putting dollars in the hands of those most likely to spend it.

Unless the Government makes a permanent real increase to the Jobseeker payment, Australia's unemployed are set to end up back on the previous $40 per day income, which given our current economic situation, may be unsustainable.

If you need urgent help with money post-March, or even before then, head to ASIC’s MoneySmart for a list of free resources you can contact for urgent help with money.

Photo by David Jackmanson on Flickr

Harry O'Sullivan

Harry O'Sullivan

Denise Raward

Denise Raward

Harrison Astbury

Harrison Astbury