It’s essentially a battle of mortgage serviceability versus housing affordability. The two are better explained in this article here. However, we’re here to add fuel to the fire, to pit Millennials (1980-1995) against Baby Boomers (1945-1964) once again, and determine whose moaning is more justified. Nevertheless, let’s find out who’s had it harder, while also not forgetting about Gen X (1965-1979) along the way, along with a brief mention of Gen Z (1996-2010ish).

Who Had It Easier Buying a Home - A Case Study

You can look at data all day, but the person you’re arguing with at the family barbecue isn’t going to see sense. Instead they’re going to use their own experiences to determine which generation had it easier buying a home. To quote Mark Twain, “Never argue with an idiot. They will only bring you down to their level, and beat you with experience”. So let’s look at a case study.

Photo: Harrison Astbury

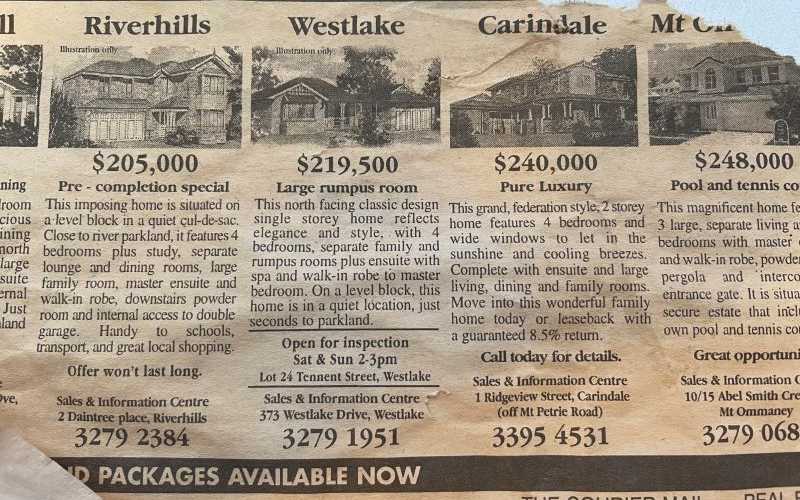

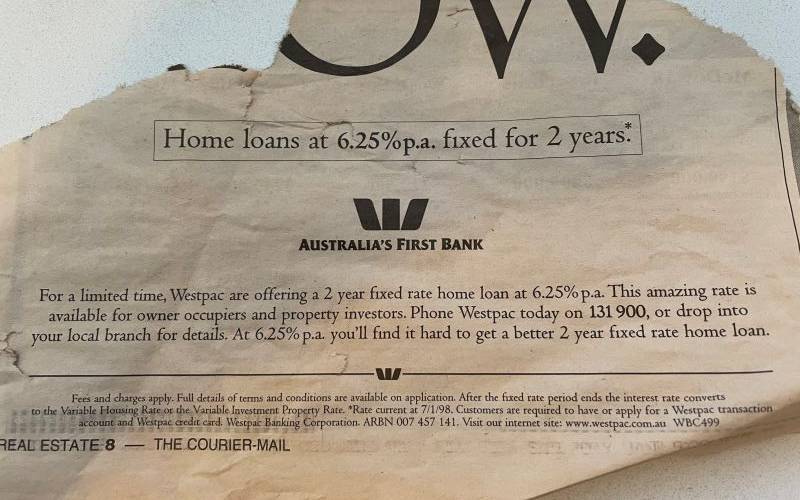

A newspaper clipping from Brisbane’s Courier Mail from 1998 shows some eye-opening information. On one side is a list of newly-built houses, and on the reverse side is a mortgage ad from Westpac. Assuming you were 30 in 1998, that places you in the Gen X generation.

Photo: Harrison Astbury

Let’s focus on the $240,000 ‘pure luxury’ house in Carindale - a suburb about 10km southeast from Brisbane CBD. It’s a nice house in a nice suburban sprawl suburb - four bedrooms and three bathrooms on a land size in excess of 600 sq m. However, $240,000 back then was hardly considered a ‘starter home’, and judging by what it’s worth today, is not a starter home.

If you used the Westpac 6.25% p.a. two year fixed loan (comparison rate unknown), assuming you had a 20% deposit, that’s a $1,182 monthly mortgage repayment in 1998 - or about $2,035 in today’s money.

The Westpac ad also says to consider the extra fees, which this calculation did not account for.

Aside from the real estate ad ‘promising’ 8.5% annual returns, which is decidedly dodgy, the house price estimate today is $1 million (according to Onthehouse and Domain).

If you again had a 20% deposit ($200,000), the mortgage repayment on a 1.99% advertised rate would equate to $2,953 today.

Wage data is hard to compare among different generations as the Australian Bureau of Statistics has changed its methodology and collection criteria throughout the years. However, based on this rough example, buyers today would be worse off in terms of the monthly payment, as well as building a deposit.

Housing Affordability - Baby Boomers v Gen X v Millennials

Below are a few key indicators, using a general midpoint in the generation, and using a home buying age of about 30.

Data Sources: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Reserve Bank of Australia, Australian Securities & Investments Commission, Australian Institute of Family Studies

Interest Rates & Mortgages

Here’s the thing about interest rates - they’re highly variable. And whenever someone brings up sky-high interest rates as reason for it being harder to service a mortgage in decades past, consider that 17%-ish interest rates were seen only for a few years from around 1987 to 1990. Sky-high interest rates were a catalyst for the 1990s recession, but by 1992, rates had stabilised to about 11%.

If your timing was unlucky enough that you bought a home during this period, then you’d have a fair cause for complaint.

-

Assuming Boomer borrowers had a 20% deposit on the average price in 1992 ($121,260), that means you’re borrowing $97,000, totalling a $1,383 monthly mortgage repayment on a 30-year term at 17%. This figure equates to $2,681 in today’s money.

- If borrowers held on for a few years, they could ride out the storm. The late interest rate of 8.75% in 1994 equates to $763 per month ($1,425 in today’s money) - in just two to four years, mortgage payments on the average home price decreased by nearly half.

Baby boomers are also an incredibly wide-ranging generation, with birth years from 1945 to 1964. A lot happened in that span, including unparalleled economic growth post-World War II, and no notable recessions until the oil crisis of the early-1970s. It’s impossible to tar all Boomers with the same brush, though those buying in the late 80s or early 90s understandably would have faced some challenges with the high interest rates.

On the flipside of the coin are Millennials and record low interest rates, with the RBA cash rate at 0.10% in late 2020.

-

Assuming a Millennial borrower had a 20% deposit on $690,200, that means they’re borrowing $552,160. Using the late-millennial standard variable rate of 4.52% in 2020, that equates to $2,804 per month.

However, 4.52% sounds high - that’s because the Reserve Bank didn’t start measuring discounted variable rates until June 2004. Frankly you’d have to be unlucky to be on the standard variable rate (SVR) these days. For reference, ASIC says the average mortgage rate as of November 2020 is 2.54%.

Chief customer officer of Aussie Home Loans, David Smith, said at the end of the day it doesn’t really matter who had it harder.

“The reality is that buying a property has always come with challenges and it’s all relative for every generation. However, there has never been more options, government incentives, experts, and information to help people get into the property market than today. So, arguably today’s generation are far more informed and supported to get in the market,” he said.

Who wins this debate?

It’s a wash. If you’re a late Boomer, you’d probably have faced higher interest rates, making any mortgage payments harder to swallow at least for a few years. On the flipside, the Millennial generation has a steeper mortgage repayment thanks to a high home price, yet the interest rates are low. The risk with younger generations, too, is being saddled with debt while interest rates are at rock bottoms - any increase in the rate could present a few problems.

If you’re an early Boomer, or a Gen Xer, you’re probably feeling like a winner in this scenario, though buying a home is hardly a cakewalk no matter what your generation.

Home Prices & Deposits

House prices, and the time it takes to save a deposit, are arguably the bigger factors in the housing affordability debate. This is where younger generations are at a disadvantage, but once they’re in the nightclub (paid for the deposit) they get relatively decent mortgage affordability. Boomers and Gen Xers, on the other hand, paid a lower entry fee, but higher fees for drinks and meals once inside the nightclub.

Domain research indicates that despite the slight COVID-19 downturn in house prices, it took two months longer for borrowers in Sydney to save for a house deposit than it did a year ago. Sydney is the city that takes the longest for those aged 25-34 to save for a ‘starter house' deposit, at six-and-a-half years. It’s not rosy in Melbourne, either, taking six years to save for one, which is nearly a year-and-a-half longer than it took just five years ago.

Traditionally a 20% deposit has been the goal, which is the threshold lenders use to not charge borrowers lenders mortgage insurance (LMI). However, a recent advent in government assistance has been the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme (FHLDS). This is a program designed to allow first home buyers to use a 5% deposit without paying LMI, as the government guarantees the remaining 15%.

However, there are a couple of criticisms associated with the FHLDS and other associated schemes:

-

Like many government grants and handouts, there are question marks on if they actually address affordability. Instead, it’s argued that the programs induce demand, pushing prices higher.

-

The fact that lower-deposit home loans tend to have higher interest rates. Reserve Bank lending data from November indicates average owner occupier interest rates for LVRs 80% or below was 2.54%, while borrowers with smaller deposits faced interest rates of 2.59% on average. Add to the fact that you’re paying interest on 95% of the home’s value, instead of 80%, and the end result over 30 years could mean thousands extra in interest paid on the mortgage. Borrowers have to weigh this up with any potential capital gains, which are not guaranteed, despite what some people say.

Speaking of the HomeBuilder grant and grants more broadly, Westpac senior economist Justin Smirk said the scheme is often baked into the cost of new housing.

“The big surprise in the December (2020) quarter was the rise in dwelling prices. While history tells us that any form of assistance purchasing a house ends up flowing through to house prices, we had thought that the magnitude of grants would have been significant enough to provide a meaningful offset,” he said.

“The main surprise compared to our forecast was how the surge in housing demand lifted dwelling prices to swamp the benefit of the Home Builder Grants. In many capital cities developers were able to lift prices in excess of the value of the grants, even in Perth and Hobart were the Federal Grant ($25,000) was supplemented by state government grants ($20,000).”

Who wins this debate?

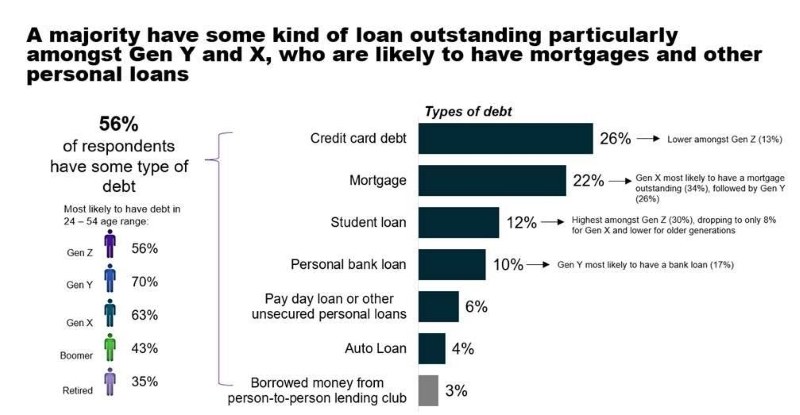

Younger generations are clear losers in regard to house deposits and saving for one. While there are a lot more government grants these days than there were 30-40-50 years ago, it’s unclear if they actually affect affordability. Handouts help an individual with their own home, but more broadly, they induce demand, which pushes up prices further. In addition, research from FIS indicates Gen Xers are most saddled with mortgage debt, as seen in the infographic below.

Source: FIS

Wages & Savings

Wages are incredibly high compared to 30-40 years ago, even accounting for inflation. However, wage growth has slowed since the Global Financial Crisis, with real wages even going backwards in 2020. Wage growth, too, has been led in large part by mining, and financial services - other sectors were more mixed.

Leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, savings ratios were incredibly low. However, as seen in many crises, households tighten their belts and save for a rainy day. Fiscal stimulus throughout 2020 saw the savings ratio climb to levels not seen since 1974, when the oil crisis was in full swing.

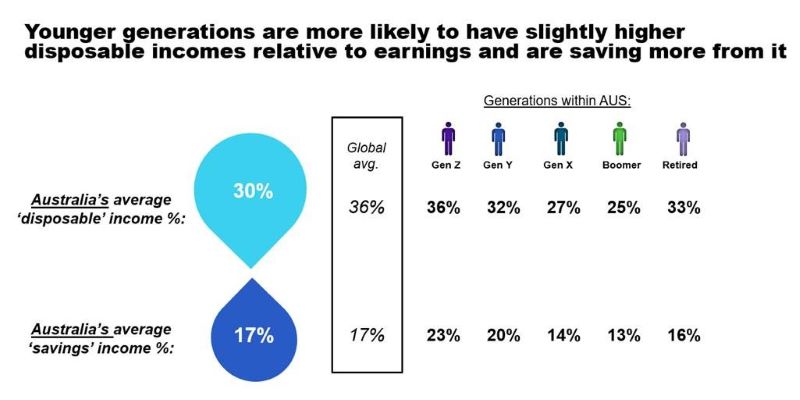

Research from FIS indicates Gen Z are the best savers, at 23%, followed by Gen Y/Millennials at 20% of income. Disposable income among younger generations was also highest, presumably because they’ve taken on fewer big debts such as a mortgage or car loan.

A survey of 1,600 Australians commissioned by rideshare service DiDi also found 52% of Gen Z saved at least 10% of their income, as opposed to 31% of Boomers, 49% of millennials, and 43% of Gen X. Nearly half (45%) of millennials are also putting their savings towards a house deposit, at least ten percentage points more so than any other generation.

However, one major negative of a low interest environment is that interest rates are lower on traditional savings methods, such as savings accounts and term deposits. This has pushed savers to look at the stockmarket, as Stockspot CEO Chris Brycki explains:

“Now with interest rates at close to zero, younger people need to look at alternative ways of growing their savings … We’ve definitely seen a big spike in enquiries and applications from people who feel frustrated about the returns their savings are getting … For the younger generation saving up, investing is becoming more popular as an alternative to leaving money in the bank. It does come with some extra risks but they can be managed by having a well diversified portfolio, low fees and a time horizon of at least a few years.”

Conversely, as seen in the infographic above, younger generations are more likely to be saddled with student loan debt. Many Baby Boomers received ‘free’ university tuition, with the Whitlam Government abolishing fees in 1974, but it’s also important to note the highest marginal tax bracket as of the early 1980s was 60%.

The advent of compulsory superannuation in the early 1990s also acts as forced savings scheme for retirement, which many Boomers did not get access to for most of their working lives. However, the counter-argument to this is that there is some evidence to suggest higher rates of super equate to lower wage growth - pick your poison.

Employment is another interesting one, with unemployment spiking in the early 1990s thanks to the recession. However, in the 1980s, underemployment was incredibly low, hovering around the 2% mark. Underemployment, which is a measurement of employed people who want more work, has been climbing steadily since about 2008, thanks in part to the gig economy, and changing labour conditions.

Who wins this debate?

Gen X seem to be the biggest losers, with the most justified cause for complaint. Unlucky Gen Xers were hit with high levels of debt, negligible wage growth, and increasing underemployment along with a lower savings ratio, affecting their ability to buy a home. Later Boomers also have a dog in the fight, with lower wages, as well as high unemployment in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In the middle are Millennials, with higher house prices and arguably rockier employment, but by some measures a higher disposable income. Earlier Boomers tended to win out once again, with relatively stable employment and incredibly low underemployment, as well as free university tuition for a large group of people, provided you weren’t drafted into the Vietnam War and sniped by the VietCong, or accidentally napalmed.

Source: FIS

Dual Income Households

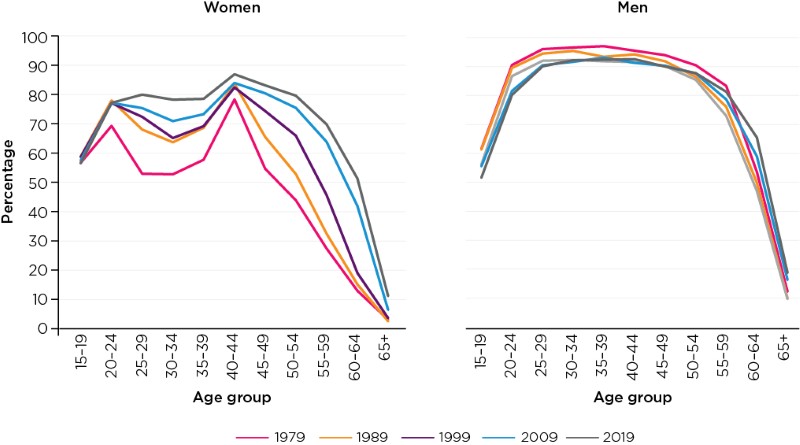

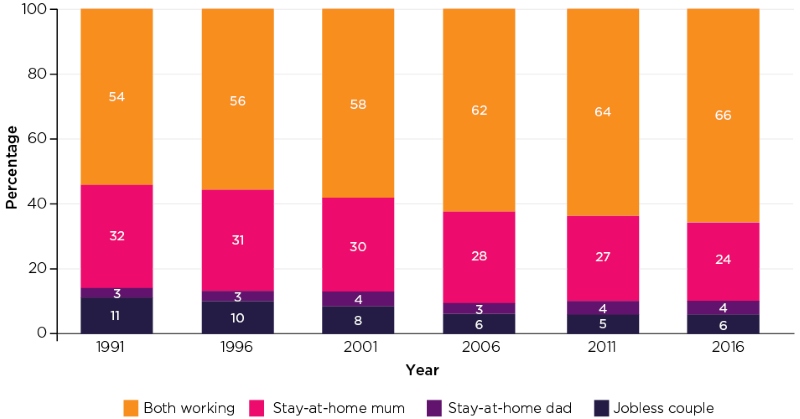

According to Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS), just over half the number of parent households earned two incomes in the early 1990s. By the mid-2010s, that figure was more like two-thirds.

An argument to make is that it was harder to buy a home on one income, especially considering the median wage back in 1994 was $1,250 (adjusted for inflation). However, there’s problems on the flipside of that argument, too.

In 2016, research house Roy Morgan said: “More than two-thirds (67.2%) of owner-occupied mortgages are now held by households with two incomes, presenting some problems if one decides to either drop out of the workforce or becomes unemployed.”

“This analysis has shown that the loss of an income in a two income-household has more impact than a doubling of interest rates,” Roy Morgan industry communications director Norman Morris said.

Women still drop out of the workforce in prime fertility years from 25 to 30, however the curve is flattening, as seen in the AIFS-compiled labour force participation breakdown below.

Source: AIFS

If both parents are on full-time wages, the likelihood of paying for childcare increases, too. Childcare is often a significant hit to the budget - consumer price inflation (CPI) data indicates childcare made up nearly half of the 0.9% inflation figure in the December 2020 quarter.

In 2004, Elizabeth Warren, more famously known as being a 2020 US presidential candidate, penned a book titled ‘The Two Income Trap’, which opined that dual incomes and rising living costs present a greater risk to households than single incomes. Ms Warren also argued that dual income families in this generation have less disposable income than single income families a generation ago.

“Even as millions of mothers marched into the workforce, savings declined … Instead, families were swept up in a bidding war, competing furiously with one another for their most important possession: a house in a decent school district,” Ms Warren wrote.

Professor Todd Zywicki in his critique of Ms Warren’s research also opined that the increased tax burden mitigates the effect of two incomes, more so than increased mortgage payments.

“The increase in tax obligations is over three times as large as the increase in the mortgage (the supposed driver of the 'two income trap') and about double the increase in the combined obligations of mortgage and automobile payments,” he said.

“This also leaves aside the peculiarity that the 2000s family is paying $9,670 in new child care and $2,860 in new automobile expenses supposedly to meet a $3,690 increase in mortgage expenses, the supposed driver of the model.”

It’s important to note that this is a US-focused research, but the same could be argued for Australia, too.

Who wins this debate?

This is decidedly a chicken-or-the-egg debate. While higher house prices may necessitate a dual income, women still leave the workforce in child-rearing years, which could increase risk of mortgage stress. An important note, is that sexist attitudes affected Boomers, as many women were unable to sign a mortgage by themselves without a husband or partner co-signing until well into the 20th century. Calling this one a tie.

Source: Australian Institute of Family Studies

Savings.com.au's two cents

Buying a home is hardly a walk in the park, no matter how old you are, or which generation you are from. It’s probably the biggest financial decision you’re going to make in your life.

However, the debate today is very black and white, and unnecessarily pits older people against younger people, defined by arbitrary generational brackets. The truth is, there’s a lot of nuance in the debate, because each individual case is different. While you can use averages and all manner of data, they don’t paint a deep enough picture.

Though, if you were to generalise, later Boomers and very early Gen X had a hard time with high interest rates. Gen Y/Millennials have to deal with much higher house prices, but lower interest rates, which might not be enough to offset the high barrier to entry i.e. obtaining a deposit.

And sandwiched in the middle are Gen Xers, with their nihilistic grunge music from Nirvana and Pearl Jam. They seem to be getting pulled in all directions, with a mixture of slight lack of affordability, hardly-inspiring interest rates, and lack of government handouts. And let’s not forget Gen Z. Sorry kiddo, better make it big on TikTok, because you look screwed.

Earlier Boomers you could argue had a decent blend of moderate interest rates, plus much lower house prices. But the world around the 1960s and 70s was much different back then - many women couldn’t even get a home loan on their own! And even then, it’s not like an earlier Boomer could just walk into a bank and have Oprah a lending specialist go ‘You get a house, you get a house!’

The best two cents we can give is to log off social media, and don’t buy into generational debates. If you want a house, ignore everything, and work hard. If you don’t agree with a housing policy, vote accordingly or write to your local Member or Minister. But for now, strap in, and feel the Gs.

Photo by Hermes Rivera on Unsplash

Ready, Set, Buy!

Learn everything you need to know about buying property – from choosing the right property and home loan, to the purchasing process, tips to save money and more!

With bonus Q&A sheet and Crossword!

Harrison Astbury

Harrison Astbury

William Jolly

William Jolly