To put it simply, the gold standard refers to currency backed by gold - more specifically currency backed by a Reserve Bank’s gold reserves. This happened in both the United States and Australia, and many other countries.

In the United States, at least, you (or a country) could exchange a dollar note for its equivalent weight in gold - at one stage it was pegged at US $35 an ounce during a period in the mid-20th century called the Bretton-Woods era. However this was a fractional reserve system, not a full reserve, which we'll get into later.

In the UK, the pound was at one stage backed by silver, which is why it’s called ‘The Pound Sterling’, and later backed by gold. Australia followed its bigger brother as its currency was pegged to the GBP.

Called ‘pegging’, currency was pegged to the price of gold, and the theory was you could at any time exchange that money for gold. You don’t have to fully-peg currency, either - it could be half-pegged for example. This effectively doubles the money supply, but lessens its value - a form of inflation. This is also called a fractional currency, as was the case with Bretton Woods.

The gold standard is pretty much the ultimate in libertarian or small government groupthink, as it largely eliminates the key modern roles of central banks. This includes monetary policy setting and bond purchases, which affects the interest rates of home loans and savings accounts, unemployment, wages, inflation…basically everything. Inflation is the big one, which we’ll talk about later.

Its backers will always be unswayed, and its detractors will always support the more ‘elastic’ fiat currency. While the middle of the 20th century provided immense financial prosperity and stability - hello Baby Boomers - it’s hard to say whether this was due to support from the gold standard. Nonetheless, it’s easy to look at the gold standard through rose-coloured glasses, but it’s unlikely any countries will ever return to it. The gold standard today, for all intents and purposes, exists as nothing more than an academic exercise.

Inflation in the post-Covid era

Inflation has hit 30 year highs in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic, which brought about loose economic policy.

The main argument for the gold standard is that it creates another gap between a few humans pulling levers and the economy. It promotes real savings, rather than a debt-driven economy used to fuel the endless quest for (GDP) growth.

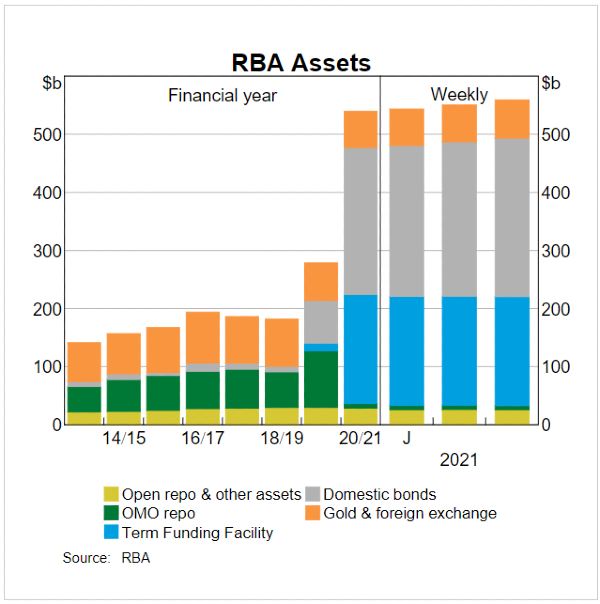

Australia’s Reserve Bank holdings peaked at nearly $700 billion in ‘assets’, an uptick of nearly half a trillion from 2020 to 2021. It bought $330 billion worth of government bonds, and enacted the $188b Term Funding Facility for banks to pay off in three years. The RBA’s cash rate target also sat at 0.10% for 18 months, making money cheap.

Put it this way, if you got 100 Mars Bars on sale at $1 each, you’d likely savour them less than if you bought a third of the them at $3 a pop, cherishing every bite.

In this sense, inflation is a measure of too much money chasing too few goods.

And now Australia has a lot of Mars Bars, with quarterly annualised inflation peaking at 7.8% in the December 2022 quarter - a 30-year high (apart from when GST came in 2000).

However just because inflation has spiked for a short period doesn’t mean the gold standard would eliminate all the problems.

Josh Bareham, Financial Adviser at My Wealth Solutions, said it’s easy to look at the situation without nuance.

“When you look at inflation statistics historically while on average it was slightly lower, it was far more volatile during the times of the gold standard - including the transitional Bretton Woods period from the 30s to 70s - compared to the present fiat currency era," Mr Bareham told Savings.com.au.

“In fact one of the major reasons why countries made the decision to remove it was due to an inability to control inflation effectively.

“Another issue that you run into with a gold standard is that if money is linked to gold then so are prices of goods and services. This means that the amount of gold in existence and rate of mining new gold directly impact the money supply and further to that, cause volatility in prices, with inflation or even deflation.

“In the modern day and age, long term stability in inflation is far more favourable than the extreme volatility that was seen during the periods of the gold standard.

“Coupled with the likely impossible volume of gold that would be required to mine to keep pace with the amount of money printed in recent years, there doesnt seem to be a favourable argument for it."

What is fiat currency?

The virtual opposite of the gold standard is ‘fiat’ currency - no that’s not a small Italian car. Fiat currency is basically what all currency is based on nowadays - its value is based on exchange and nothing more than the promise that the government will do its job. Any money created is essentially done so by a central bank ‘out of thin air’.

In this way, fiat currency is generally more elastic, but can be at the hands of the government or central bank of the day. If government or central bank instability rocks a nation, the value of its currency can plummet: Think of Germany’s Weimar Republic, Venezuela or Zimbabwe - and more recently, Turkey or Argentina.

Even in moderate examples, such as Australia, the remit of many central banks is to adjust monetary policy to affect inflation.

If you’ve ever had an annoying six year old ask “But why do we use this money?” or “Why is this paper note WORTH something?” you’ve probably been stumped. The gold standard, however, means currency is based on something, which can be easier for some people to wrap their head around.

The gold standard in Australia - a brief history

Much of the literature surrounding gold standards relates to the United States. But we Australians have had a relatively fleeting relationship with currency tied to gold. All up, some sort of gold or silver backing lasted just over 100 years.

According to the Reserve Bank of Australia, in 1825 under British rule, the Australian colonies had legislated a sterling currency - meaning currency backed by silver. Australia’s first gold coins were minted in 1855 at the start of our gold rush. The number of notes a bank could issue was limited by their gold reserves - so you can see why there was a ‘gold rush’.

However, at the outbreak of the First World War, the British Empire suspended use of the gold standard to more easily fund its operations, which brought about inflation. After, the British Empire could have continued its ‘fiat’ currency, but returned to the gold standard, which had a strong deflationary effect.

In the words of A.C. Davidson, former General Manager of the Bank of New South Wales (now Westpac), this ended up being “probably the greatest achievement that has ever been known in economic history.”

“The return to the gold standard brought many and great advantages. The most was that the return to the gold standard reduced the great difficulties attached to external trade during the period of inflation,” Mr Davidson wrote in The Australian Quarterly in December 1929.

It can be thought to promote trade because an ounce of gold is an ounce of gold and is valued pretty much no matter where you go - a country's fiat currency? Maybe not so much.

Australian currency was backed by gold until 1932. Monetary policy from 1932 through to the 1970s had the currency pegged to the Great British Pound Sterling, which at the time also stopped being backed by gold in 1931.

In 1966, Australia introduced the decimal currency system and changed the currency to the dollar. In 1967 it was then pegged to the US dollar. The Hawke-Keating Government in 1983 then ‘floated’ the dollar, making it freely able to ebb and flow on global exchange markets.

Are any currencies still backed by gold?

At present, no currencies in the world are backed by the gold standard, whereby consumers can hand in their currency for an equivalent piece of gold.

Switzerland appeared to be the last country to have some form of gold standard but severed the direct tie between currency and gold in 1999.

Gold standard in economic turmoil

History shows even countries that were most ardent supporters of the gold standard - the United States - suspended the pegging in times of crisis.

This happened in the Great Depression, but the jury’s out on whether it was a direct causation.

Writing for The Conversation, Professor of International Economic Affairs at Tufts University, Dr Michael Klein, said it was odd that there are advocates for the gold standard today.

“Going back to a gold standard would handcuff the Fed in its efforts to address changing economic conditions through interest rate policy. The Fed would not be able to lower interest rates in the face of a crisis like the one the world faces today, because doing so would change the value of the dollar relative to gold,” Dr Klein said.

“The onset of the Great Depression finally forced the U.S. and the other countries that still pegged their currencies to gold to abandon the system entirely.

“Economist Barry Eichengreen has found that efforts to maintain the gold standard at the beginning of the Great Depression ended up worsening the downturn because they limited the ability of central banks like the Fed to respond to deteriorating economic conditions.

“For example, while central banks today typically cut interest rates to boost a faltering economy, the gold standard required them to focus solely on keeping their currency pegged to gold.”

Famed economist Milton Friedman offered a more balanced theory in that the US Federal Reserve at the time of the Great Depression failed to pump adequate reserves into the banking system to stave off a collapse.

However, Associated Scholar at the libertarian Mises Institute, Frank Shostak, disputed Friedman’s theory in a 2020 report.

“The Great Depression of 1930s occurred because of the Fed’s loose monetary stance from October 1920 to August 1924, which undermined the pool of real savings,” Mr Shostak said.

“The sharp fall in the money supply from 1930 to early 1933 was in response to the collapse of this pool.”

“Economic depressions are not caused by the collapse in the money stock but come in response to a shrinking pool of real savings on account of the previous easy monetary stance of the central bank.”

The ‘Bretton Woods’ era

Adopted in 1944 was a global monetary agreement called the Bretton Woods agreement. Several allied countries agreed to use the US Dollar as its reserve currency, which in turn was backed by gold.

Under the Bretton Woods system, most countries settled international balances in the US Dollar. The US Government also agreed to redeem other central banks' dollar holdings for gold at a fixed rate of $35 an ounce.

Under what was effectively a one-currency world with many central banks cooperating, this coincided with a relatively stable period free of economic crises for about 30 years.

However this posed a conundrum in that the United States itself couldn't hand in its currency for gold; only the allied countries could. Many countries saw the risk of this, and saw the US Dollar as overvalued due to the state of the economy at the onset of the Vietnam War, and started handing in their US Dollars for the gold.

The only problem was, the US didn't have enough gold to piece-by-piece account for all the currency exhanged. This pretty much undermined the United States' power and influence.

President Richard Nixon, not liking this power shift, effectively ended this key component of the agreement in 1971, dubbed the ‘Nixon Shock’.

Many backers of the gold standard cite this period as a good reason to go back to gold-backed currency, because shortly after was an oil crisis and a long period of ‘stagflation’.

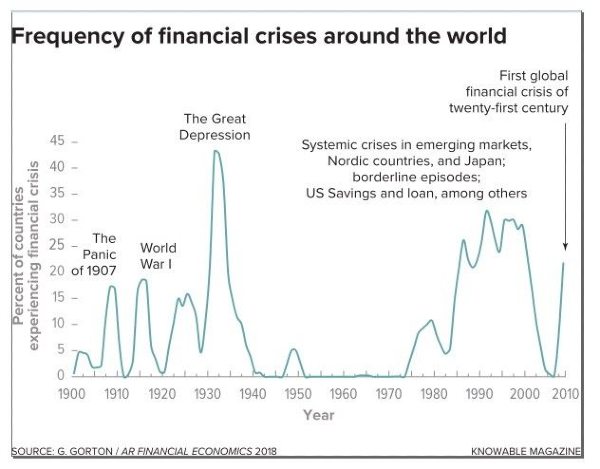

“Readers will clearly see the big flat spot in the middle where there were almost zero financial crises,” said Jeremy Britton, CFO at Boston Trading Co.

“This halcyon period was the Bretton-Woods era; where the world used the gold standard after WW2, up until 1971 when the USA removed gold backing.

“Behind the curves and bumps of the chart, there are millions of people losing their jobs, their life savings and their homes. Entire governments have teetered on bankruptcy or massive QE [quantitative easing], followed by massive inflation.”

The Bretton Woods system was a bastardisation of a pure gold standard where citizens could exchange money for a piece of gold, but is the most recent example of a 'gold standard'.

Gold standard and inflation

Inflation is a core component in today’s world economies. Most developed nations' central banks try to keep inflation levels in a ‘healthy’ band at an annualised rate of about 2-3%. This is thought to spur on wage growth, keep unemployment low, and a variety of other factors.

Central banks can toy with measures to increase or decrease inflation to change economic trajectory.

However, for backers of the gold standard, this is hell on earth because a strong currency is thought to lead to a strong and stable economy.

Gold advocates ‘As Good as Gold’ say that many Australians are confused about the true strength of their currency.

“[Australians] have failed to acknowledge a sustained collapse in the dollar’s value over, at least, the past two decades,” its chief economist John Adams said.

Mr Adams says it’s not gold that has risen in value, but that the purchasing power of the dollar has fallen.

“In this context, the value of the Australian dollar has experienced a sustained and dramatic fall of 76.2% over the past 21.5 years since the onset of the Asian Financial Crisis relative to ‘hard money’ such as physical gold,” he said.

“For example, at the start of the Asian Financial Crisis on 2 July 1997, one Australian dollar was equivalent to 6.38% of a gram of gold, only to be worth 1.56% of a gram of gold on 31 December 2018.”

However, Tuft’s Dr Klein generally disputes the inflation argument.

“Arguments for returning to a gold standard reappear periodically, typically around times when inflation is raging, such as in the late 1970s,” he said.

“Its backers assert that central bankers are responsible for surging inflation, through policies like low interest rates, and so the gold standard is necessary to rein them in.

“It is particularly odd, however, to advocate for a gold standard at a time when one of the main problems a gold standard would supposedly address – runaway inflation – has been low for decades.”

But that’s all changed in the post-Covid era.

Gold has intrinsic value

Gold is a lot more than just a pretty asset. It is highly conductive, which makes it useful in small amounts in electronics and medical devices. Gold is used in connectors, switch and relay contacts, connection wires and other components.

Tiny amounts of gold can be found in mobile phones, calculators, GPS devices and more. On the medical side of things, gold is used in dental fillings. It is also used as a drug in small doses to treat conditions such as rheumatoid arthiritis.

The theory favoured by ‘doom and gloom’ types is with a healthy gold reserve, countries can stave off a disaster or zombie apocalypse. Because, even if currencies fell to hell in a handbasket, consumers could still use gold to buy their way out of trouble.

Australia has a lot of gold and gold reserves

Australia is one of the richest gold mining countries on the planet, and our gold reserves are pretty healthy too, especially when compared to other countries with similar populations. We have the world’s largest known gold reserves at 9,500 tonnes or 17% of the world’s estimated gold reserves. In 2023 alone Australia is projected to produce 379 tonnes of gold.

Since 1997 RBA financial reports indicate it has consistently held about 80 tonnes of gold, or 80,000kg. While this pales in comparison to powerhouses such as United States (8,133 tonnes), or Germany (3,361 tonnes), it’s a lot higher than other developed countries such as Ireland (6 tonnes), and Canada which has zero gold reserves. Canada’s central bank sold the last of its gold in 2016, which has some detractors spooked.

Drawbacks of the gold standard

But there’s still not enough gold!

Even with nearly 80,000kg of gold reserves, and with a sky-high gold price, that’s probably still not enough to cover currency and the rest of its balance sheet. As of early July 2023, the RBA had more than $94.5 billion worth of gold on its balance sheet, an increase of $800 million.

However this increase was more due to the fluctuation of the Aussie Dollar and the spot price of gold, rather than the RBA holding more gold. This would theoretically be less volatile if the currency was pegged to gold.

This also pales in comparison to the amount of currency currently in circulation - the RBA says as of June 2022 there was $102.3 billion worth of banknotes on issue.

And aside from currency, gold would need to form the majority of a Reserve Bank’s assets. In 2020 the Reserve Bank grew its balance sheet ‘out of thin air’ to cushion the effects of lockdowns led by the Covid crisis. It peaked at $700 billion worth of assets, with a large portion of this in domestic bonds.

The Reserve Bank would need to increase its gold reserves around one hundred-fold to account for this upsized balance sheet. However, that’s where our gold mining could prove effective, producing 350 tonnes in 2020 alone.

The RBA increasing its balance sheet (with no gold to tie it down or act as a moderator on its operations) caused inflation to peak at 7.8% in the December 2022 quarter. Inflation pretty much means your currency is devalued as your dollar gets you less far than last year.

Gold has significant handling and storage costs

“Gold is bulky and expensive to transport across borders for settlement,” Mr Britton said.

“$100 million worth of gold needs a dozen people in its entourage: drivers, pilots, armed security guards, and so on.”

And then you’d need somewhere to store it. Banks have vaults, but the vast quantity of gold needed today would mean a significant bolstering of its security systems. Many companies and countries offer to store gold securely, but this comes as an added cost.

The RBA holds most of its gold at the Bank of England, and conducts regular audits into the quality of its reserves. This alone requires manpower and financial outlay.

Gold is not infallible

Australia alone mines in excess of 300 tonnes of gold every year. Every extra tonne added to the stockpile devalues current gold a little bit, which is a form of inflation in itself.

“Gold supply is marginally inflationary: around 2-3% new supplies of gold are brought onto the market each year from new mining projects, devaluing existing supply ever so slightly,” Mr Britton said.

“Gold can be inflated via the use of partially backed currency, the creation of gold ETFs and other forms of 'paper gold'.

“This gives similar risks to fractional reserve banking and 'bank runs', where not everyone's paper gold can be redeemed for physical gold.”

Would we ever go back onto the gold standard?

Here’s the major caveat - backers of the gold standard usually only talk about what it was like in the good old days. Few talk about the logistics of it being re-introduced today, with gold at more than AUD $2,000 an ounce, the RBA holding nearly $700 billion in ‘assets’ it’s trying to sell down, and 40-odd years of free-floating currency.

“The pandemic helped drive up the price by 40% to [USD] $2,049 in August [2020]. As of Nov 18, it was about $1,885. Clearly, it would be destabilising if the dollar were pegged to gold when its price swings wildly,” Dr Klein said.

However, one could argue that price swings wouldn’t happen, and gold wouldn’t be so expensive and attractive in a time of crisis if the dollar was pegged to it.

National debt also poses a problem, especially for the United States, which ebbs and flows out of trade deficits, particularly with China. If you had $1 trillion in debt, you would effectively need to underwrite that with gold, as the creditor could theoretically come knocking at any moment for its gold.

Owing money to China under a gold standard would essentially mean giving gold to China, lest they also adopt a gold-backed currency too.

For supporters of the gold standard, it appears we’re ‘too far gone’ to return to using it.

Cryptocurrency the new ‘gold standard’?

A similar mindset of gold backers tends to permeate through the minds of crypto-bros and supporters.

That is, the thought that a decentralised currency is the way of the future.

For Mr Britton, CFO of Boston Trading Co, which claims to offer the world’s first crypto ETF, cryptocurrency is the new frontier.

“The world needs a Bretton-Woods 2.0 solution, as financial crises, even if not in your home country, is bad news for every world citizen,” he said.

“A billion dollars in bitcoin can be carried in a smartphone, thumb-drive or sent via email.”

That last point will probably scare the pants off most gold backers, and many people in general - having currency that could be wiped from the face of the earth at a moment’s notice.

That said a few countries have now included bitcoin as some form of reserve currency.

“It is interesting to note that the countries which benefited the least from the USD hegemony are the first to embrace bitcoin as a reserve currency: El Salvador, Iran, Mexico, Paraguay, Cuba and Brazil,” Mr Britton said.

“Which of the erstwhile 'poor' nations will become a new economic power?”

However, bitcoin’s wild swings arguably make it more infeasible than gold for a country’s reserves. Bitcoin can fluctuate daily by more than 20%. And one tweet, from someone such as Elon Musk, can crater the price.

Gold-backed cryptocurrencies

There are a few cryptocurrencies that are tied to gold. The theory is they provide more stability than traditional crypto, while also potentially serving as a worthwhile investment and currency with a lot of liquidity. Some are:

-

Asia Broadband (AABB) Gold Token

-

Tether Gold (AUXt)

-

Perth Mint Gold Token (PMGT)

The last one is a true-blue Aussie brand from the reputable Perth Mint. Gold tokens are backed by the Australian government, and token holders are given certificates to prove their holdings.

First published on September 2021

Photo by Jingming Pan on Unsplash

.jpg)

Denise Raward

Denise Raward

Harry O'Sullivan

Harry O'Sullivan

Brooke Cooper

Brooke Cooper

Rachel Horan

Rachel Horan